Sul blog di HERBALISTS WITHOUT BORDERS il primo contributo dall’Italian Chapter in italiano (anche in versione inglese), l’articolo di Pierluigi Campidoglio su “Arnica, Calendula, Bellis” che qui pubblico con piacere.

(Per il blog e informazioni sull’organizzazione HERBALISTS WITHOUT BORDERS VISITA: http://herbalistswithoutborders.weebly.com/blog)

Arnica, Calendula and Bellis

di Pierluigi Campidoglio*

Sono tre generi botanici appartenenti alla famiglia delle Asteraceae (o Compositae, nomen conservandum), uno dei due generi più numerosi tra le Spermatophytae (piante che si riproducono per seme), insieme alle Orchidaceae.

A causa del gran numero di specie in essa contenute, la famiglia delle Asteraceae è stata suddivisa in 13 sottofamiglie e diverse tribù e sottotribù. Arnica, Calendula e Bellis appartengono alla sottofamiglia delle Asteroideae e a tribù differenti. Tutte hanno flosculi (fiori che compongono l’infiorescenza complessa) sia ligulati sia tubulati.

Questi tre generi e le rispettive specie più conosciute, Arnica montana, Calendula officinalis e Bellis perennis, sono considerate probabilmente i migliori rimedi per i traumi fisici ed emozionali, sia in fitoterapia sia in omeopatia. Secondo David Little, i rimedi omeopatici delle Asteraceae possono essere suddivisi in quattro gruppi (Arnica, Chamomilla, Cina e Wyethia) sulla base delle similitudini nelle modalità di azione. Tutto il gruppo dell’Arnica (che comprende i rimedi Arnica, Brachyglottis, Bellis perennis, Eupatorium aromaticum, Eupatorium perfoliatum, Eupatorium purpureum, Calendula, Erechtites, Erigeron, Echinacea, Gnaphalium, Guaco, Lappa, Millefolium, Senecio aureus) è caratterizzato da traumi, emorragie, stati settici, diatesi artritica e reumatica e co-affezioni urinarie (vedi [Vermeulen]).

Bellis perennis non ha mai guadagnato la stessa popolarità di Arnica montana e Calendula officinalis, che sono usate in ogni caso di trauma, di piccola o grande entità, ma la “umile” margherita è in realtà un rimedio piuttosto potente che può essere usato in maniera più o meno intercambiabile rispetto agli altri due, sebbene ovviamente sussistano delle differenze. In prima battuta, possiamo descrivere Bellis perennis come simile a un’Arnica che agisce più in profondità e che possiede una gamma di indicazioni un po’ più ampia.

Prima di proseguire, diamo un’occhiata a cosa sostenevano gli antichi autori a proposito di queste tre piante.

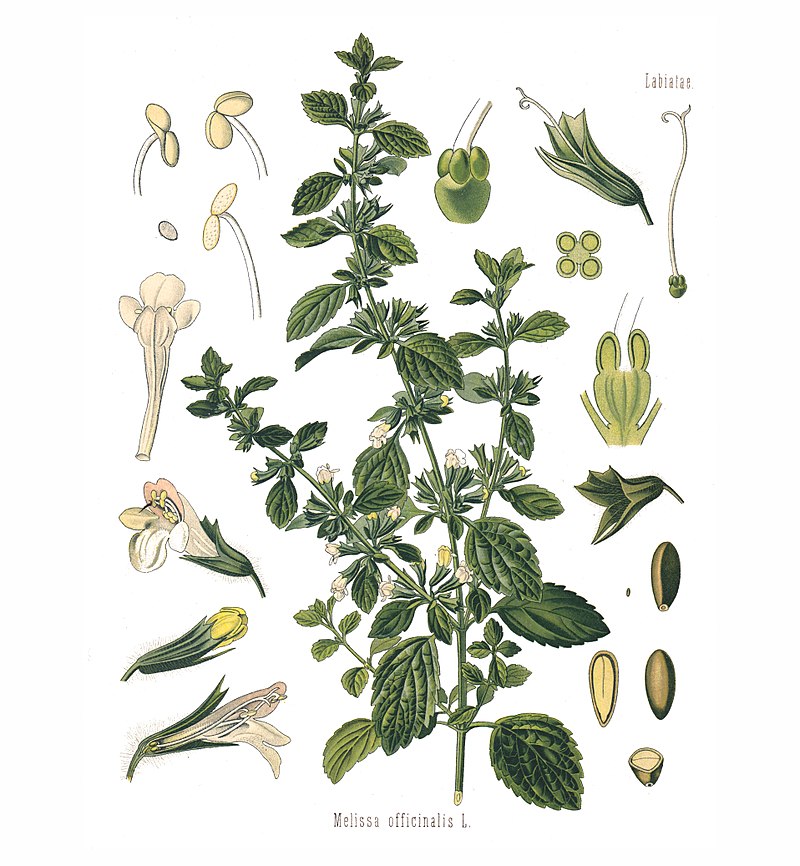

Bellis

John Gerard [Gerard], a proposito delle “piccole margherite”, riporta:

“Le Margherite piccole sono fredde ed umide, essendo umide verso la fine del secondo grado, e fredde verso l’inizio dello stesso.

Le Margherite mitigano tutti I tipi di dolore, ma specialmente nelle articolazioni, e nella gotta causata da un umore secco e caldo, se esse vengono schiacciate con un po’ di burro nuovo non salato, e applicate sul posto che duole: ma esse funzionano più efficacemente se è aggiunta della Malva.

Le foglie delle Margherite, cotte insieme ad altre erbe, solvono il ventre; e sono usate anche nei Clisteri con buon successo, nelle febbri ardenti, e contro l’infiammazione dell’intestino.

Il succo delle foglie e delle radici inalato nelle narici, purga potentemente la testa dagli umori maleodoranti, viscidi e corrotti, e aiuta nel mal di testa.

Lo stesso dato ai cani piccoli insieme con latte, impedisce loro di crescere.

Le foglie peste rimuovono i lividi e i gonfiori che procedono da qualche colpo, se esse sono pestate e applicate sopra; da che essa era chiamata nei tempi antichi Bruisewort[1].

Il succo messo negli occhi li schiarisce, e sana l’eccessiva lacrimazione.

La decozione della Margherita di campo (che è la migliore per l’uso in medicina) fatta in acqua e bevuta, è buona contro la febbre malarica, l’infiammazione del fegato e di tutte le parti interne.”

Culpeper [Culpeper], scrive, a proposito della margherita maggiore (Leucanthemum) e della minore (Bellis), nello stesso paragrafo:

“[Le Margherite] sono così ben conosciute finanche dai bambini, che suppongo sia inutile scrivere alcuna descrizione di esse. Prendi dunque le loro virtù come segue.

Governo e virtù. L’erba è sotto il segno del Cancro, e sotto il dominio di Venere, e quindi è eccellentemente buona per le ferite del petto, e molto adatta ad essere messa negli oli, negli unguenti, negli impiastri e anche negli sciroppi. La Margherita selvatica maggiore è un’erba vulneraria di gran rispetto, spesso usata nelle bevande o negli unguenti preparati per le ferite, sia interne che esterne. Il succo o l’acqua distillata di esse, o delle margherite minori, modera molto il calore della collera, e rinfresca il fegato, e le altre parti interne. Un decotto fatto con esse, e bevuto, aiuta a curare le ferite fatte nelle cavità del petto. Lo stesso cura anche tutte le ulcere e le pustole della bocca e della lingua, o delle parti segrete. Le foglie contuse ed applicate allo scroto, o a qualunque parte che sia gonfia e calda, lo risolve, e modera il calore. Una decozione preparata con esse, con erba di muro e agrimonia, e fomentando o bagnando i posti con essa calda, conferisce gran sollievo a coloro che sono affetti da paralisi, sciatica, o gotta. La stessa disperde anche e dissolve i noduli o i nòccioli che crescono nella carne di qualunque parte del corpo, e i lividi e le ferite che vengono da cadute o percosse; esse sono usate per le ernie, o altre aperture interne, con gran successo. Un unguento preparato con esse aiuta meravigliosamente tutte le ferite che siano infiammate intorno, o che, a causa di umori umidi, non riescono a guarire da tempo e tali sono quelle, per la maggior parte, che si verificano alle articolazioni delle braccia o delle gambe. Il loro succo instillato negli occhi che lacrimano di chiunque, li aiuta molto.”

Il Mattioli scrive:

“È il Bellis di più, e varie, sorti, che tre sono le distinzioni delle sue spezie, cioè maggiore, minore, e mezzano. […] Lodano tutte queste spezie i moderni per le scrofole, per le ferite della testa, e parimente per le bande delle ferite cassali penetranti nella concavità del petto. Le foglie masticate sanano le pustule ulcerate della bocca, e della lingua, e peste, e applicate le infiammazioni delle membra genitali. L’erba fresca mangiata nell’insalata, mollifica il corpo stitico, e il medesimo fa ella mangiata cotta nel brodo delle carni. Usanle alcune ai paralitici, e parimente nelle sciatiche.” [Mattioli]

Calendula

Gerard scrive:

“I fiori della Calendula sono di temperature calda, quasi nel secondo grado, specialmente quando sono secchi: sono ritenuti capaci di rafforzare e confortare molto il cuore, e anche di resistere ai veleni, ed anche di essere buoni contro le febbri malariche pestilenziali, comunque vengano assunti. Fuchsius ha scritto, Che bevuti col vino provocano i mestrui, e il loro fumo espelle le secondine.

Ma le foglie dell’erba sono più calde; poiché in esse c’è alquanta mordacità, ma a causa dell’umidità congiunta ad essa, essa non si mostra neanche poco a poco; a causa di tale umidità essi mollificano il corpo, e lo solvono se sono mangiate cotte.

Fuchsius scrive, Che se la bocca è lavata col succo aiuta nel mal di denti.

I fiori e le foglie della Calendula distillati, e l’acqua instillata negli occhi arrossati e lacrimosi, fa cessare l’infiammazione, ed elimina il dolore.

La conserva preparata con i fiori e lo zucchero presa a digiuno al mattino, cura il tremolio del cuore, ed è anche data in tempo di peste o pestilenza, o corruzione dell’aria.

Le foglie gialle dei fiori sono seccate e conservate in tutta l’Olanda contro l’Inverno, da mettere nei brodi, nelle pozioni mediche, e per diversi altri scopi, in tale quantità, che in alcune drogherie o rivendite di spezie si ritrovano barili pieni di essi, e sono venduti più o meno al costo di un penny, dimodoché nessun brodo è ben fatto senza le Calendule essiccate.” [Gerard]

Culpeper scrive:

“[Le Calendule] sono così diffuse in ogni giardino, e così ben conosciute che non hanno bisogno di alcuna descrizione.

Tempo. Fioriscono per tutta l’Estate, e talvolta anche in Inverno, se è mite.

Governo e virtù. È un’erba del Sole, e sotto il Leone. Esse rafforzano fortemente il cuore, e sono molto espulsive, e appena un po’ meno efficaci dello zafferano nel vaiolo e nel morbillo. Il succo delle foglie di Calendula mischiato con aceto, e bagnando qualunque rigonfiamento caldo con esso, dà istantaneamente sollievo, e lo allevia. I fiori, sia freschi che secchi, sono molto usati nei posset, nei brodi, e nelle bevande, per confortare il cuore e gli spiriti, e per espellere qualsivoglia qualità maligna e pestilenziale che possa dar loro noia. Un impiastro fatto con la polvere dei fiori secchi, strutto, trementina, e colofonia, applicato sul petto, rafforza e aiuta il cuore infinitamente nelle febbri, siano esse pestilenziali o meno.” [Culpeper]

Mattioli scrive:

“Vogliono alcuni dei moderni, che la Calendola […] sia la Calta di Virgilio, e di Plinio, fondandosi solamente nell’aureo colore de’ suoi perpetui fiori. […] Noi in Toscana la mangiamo nell’insalata. Scalda la Calta, assottiglia, apre, digerisce, e provoca, quantunque nel gustarla vi si senta alquanto del costrettivo: ma è cosa notoria per mille sperimenti fatti dalle donne, che provoca ella apertamente i mestrui, e massimamente bevutone il succo; ovvero mangiata l’Erba alquanti giorni continui. Il succo bevuto al peso d’un’oncia, con una dramma di polvere di Lombrichi terrestri, guarisce il trabocco di fiele. Sono alcuni, che dicono, che l’uso di quest’erba acuisce non di poco la vista: ma è ben cosa chiara, che l’acqua lambiccata dall’erba fiorita guarisce il rossore, e l’infiammazioni degli occhi distillandovisi dentro, o applicandovi sopra colle pezzette di tela di Lino. La polvere della secca messa sopra i denti che dogliono, vi conferisce assai. [alla voce: Eliotropio]” [Mattioli]

Castore Durante è leggermente più dettagliato:

“QVALITA’. È calda, & secca, & si conuien più alle parti esterne del corpo, che all’interne: assottiglia, apre, digerisce, prouoca, quantunque nel gustarla si senta c’habbia alquanto del costrettiuo.

VIRTV’. Di dentro. Prouoca i mestrui bevendosi il succhio, ouero mangiata l’herba alquanti giorni continui. Il succo beuuto al peso d’vn oncia con vna dramma di poluere di lumbrici terrestri guarisce il trabocco del fiele. Mangiasi le foglie, e i fiori vtilmente nelle insalate, & messi ne i brodi da lor buon odore, & sapore. Conferisce quest’herba ne gli affetti del cuore, nelle difficultà del respirare, & nel trabocco del fiele. Fassi dei fiori, & delle cime tenere con rosso d’ouo vna frittata, che mangiata ferma i mestrui superflui.

VIRTV’. Di fuori. L’ACQUA stillata dalli suoi fiori, & frondi leua l’infiammation de gli occhi istillatavi dentro, ò con vna pezzetta applicata, & assottiglia la vista & vale come quella del cardo santo, & della scabiosa à i mali pestiferi, & è cordiale. Sana l’herba le ferite. La poluere de i fiori messa con bambagio nel dente ne leua il dolore. I fiori & le foglie secche facendone perfumo alla natura prouocano merauigliosamente i mestrui, & le secondine ritenute nel parto. Il fiore fà i capelli flaui, facendolo bollir nella liscia.” [alla voce: CALTHA] [Durante]

Arnica

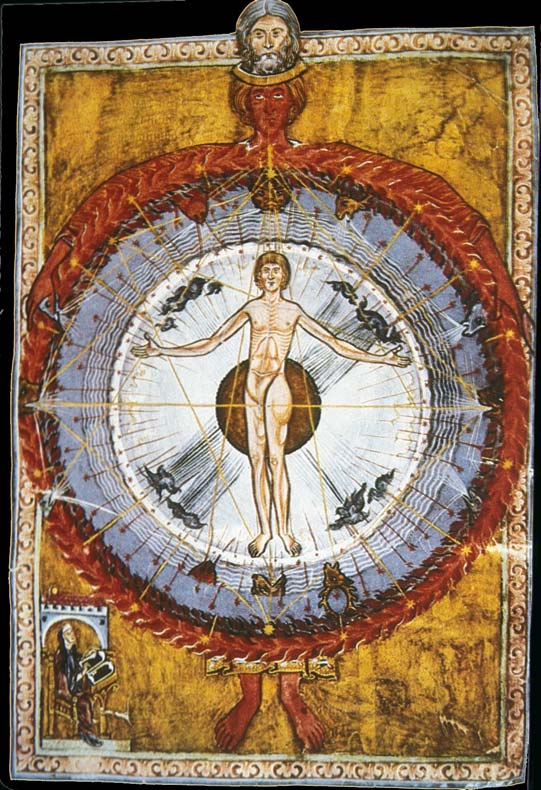

Arnica montana è attualmente una delle erbe più note, ma nell’antichità sembra che fosse molto poco conosciuta. È stata citata da Hildegard von Bingen, che l’ha chiamata “Wolfsgelegena”:

“Wolfsgelegena è molto calda e possiede un calore velenoso in essa. Se la pelle di una persona è stata toccata con l’Arnica fresca, lui o lei arderà fortemente d’amore per la persona che successivamente venga toccata dalla stessa erba. Lui o lei sarà così acceso d’amore, quasi [da essere] infatuato, e impazzirà.” (Physica)

Alcuni autori hanno associato la Wolfsgelegena all’Arnica, dato che la descrizione in Physica si adatta perfettamente a quello che sappiamo oggi dell’Arnica e, cioè, che è un rimedio topico efficace per tagli, bolle, eruzioni cutanee, e dolore, ma alcuni storici della medicina non sono certi della corrispondenza con l’Arnica o piuttosto con un’altra erba con effetti simili. L’Arnica appare citata nei testi medici solo a partire dal XV secolo, ma viene solo descritta e rappresentata. Alla fine del 1500 venne segnalata per la cura delle ferite e fu consigliata in ambito medico solo verso la fine del XVI secolo da Franz Joe di Gottinga. Benché l’Arnica fosse coltivata da tempo nei giardini, sembra che sia stata accettata nelle farmacie soltanto attorno al 1788.

In un periodo più recente, l’abate Kneipp si è espresso riguardo all’Arnica in base alle sue esperienze personali, mettendo la pianta in cima alla lista delle piante curative per la guarigione delle ferite. Nel suo libro “Meine wassen-kur” (“La mia cura con l’acqua”) del 1890 si può leggere:

“la tintura di Arnica è talmente conosciuta dovunque e usata per la cura delle ferite e in compresse […], che non mi sembra necessario spendere alcuna parola su di essa”.

Goethe beveva un infuso di Arnica quando avvertiva dolori al petto, dovuti all’insufficienza cardiaca legata all’età.

A causa della mancanza di riferimenti nei testi classici di medicina ippocratico-galenica, è difficile sapere quale fosse la natura (temperatura) tradizionalmente attribuita all’Arnica. Nonostante le incertezze sulla reale identità della pianta menzionata da Hildegard von Bingen, è verosimile che l’Arnica sia realmente “molto calda e con un calore velenoso”, date le sue proprietà (capacità di stimolazione della circolazione artero-venosa e dell’attività cardiaca; attività revulsiva, per uso esterno, e colagoga, diuretica, emmenagoga e, ad alte dosi, abortiva, per uso interno), la sua tossicità e i suoi specifici effetti collaterali (irritazione a livello gastrico con nausea e coliche, nonostante l’induzione di paralisi dei centri nervosi).

L’Arnica ha una attività analettica (ossia stimolante del sistema nervoso) e tale attività si può manifestare, in alcuni soggetti, anche alle diluizioni omeopatiche.

Differenze d’azione

Se è vero che tutte e tre le piante sono utilizzate in maniera spesso interscambiabile, specialmente in caso di traumi e ferite (anche settiche)[2], esistono tuttavia tra di loro delle differenze abbastanza importanti. La prima differenza appare evidente dagli scritti degli autori classici ed è relativa alla natura (o temperatura) delle tre erbe:

- Bellis è fredda ed umida nel secondo grado (quindi più che semplicemente fresca)

- Calendula è calda e umida

- Arnica è molto calda e contiene un calore velenoso.

Possiamo dunque affermare che, nel passare da Bellis a Calendula e quindi ad Arnica, il grado di calore aumenti in maniera abbastanza importante, tanto che Bellis è decisamente raffreddante, Calendula riscaldante e Arnica talmente calda da risultare tossica.

La Margherita ha un’azione più decisamente rivolta alla sedazione dell’infiammazione, del dolore e anche delle reazioni di tipo istaminico, per cui è particolarmente adatta ai disturbi di tipo “caldo”: infiammazione, dolore acuto, rossore, gonfiore (es., scottature, traumi dolenti, pizzichi di insetto anche con iper-reazione). La mancanza di calore nella Margherita non la rende particolarmente atta a “muovere i liquidi”: essa non ha, ad esempio, apprezzabile attività emmenagoga, né, di conseguenza abortiva. In realtà, se è vero che la pianta della Margherita è decisamente fredda ed umida, i suoi capolini contengono un certo grado di calore, tanto da risultare leggermente piccanti (ma non brucianti) al gusto. Questa proprietà conferisce ai capolini di Margherita una certa capacità diffusiva e di movimento, che rende assolutamente più complessa (e completa) l’azione della pianta quando sia usata in toto, cioè in foglia, fiore e radice insieme. Anche la Margherita, come la Calendula (v. oltre), ad esempio, può essere usata in caso di ferite settiche.

La Calendula è, come già detto, più calda della Margherita e pertanto la sua azione è decisamente più “improntata” al movimento: essa stimola, infatti, il movimento sia del sangue (da qui la sua capacità emmenagoga) sia, in maniera marcata, della linfa. Da ciò deriva che la Calendula ha un’azione importante sulla sepsi, tanto che la pratica ha mostrato la sua efficacia nel trattare anche infezioni piuttosto importanti o difficili da eradicare. La sua azione in tal senso è più da imputare alla sua capacità di agire sui tessuti e sul sistema linfatico che su una attività direttamente antibiotica. Quindi la Calendula ha probabilmente una maggior efficacia nel prevenire e curare la sepsi e nello stimolare le mestruazioni, mentre la Margherita ha un’azione antiflogistica e antidolorifica più decisa.

L’Arnica è la più calda delle tre, tanto da risultare piuttosto tossica e anche decisamente abortiva.

Al diverso grado di calore è associata anche la “profondità” di azione delle piante: siccome il calore tende a superficializzare, l’Arnica ha una affinità maggiore per i tessuti più superficiali (pelle, muscoli e vasi sanguigni), mentre la Margherita ha un’affinità maggiore per quelli più profondi (petto, addome e cavità corporee). La Calendula ha un grado di Calore intermedio e, quindi, intermedia è anche la sua profondità di azione (infatti ha un effetto importante sui liquidi corporei).

Un’altra differenza degna di nota sta nel tropismo delle piante. Culpeper sostiene che la Margherita è un’erba sotto il segno del Cancro e sotto il dominio di Venere, mentre la Calendula è sotto il segno del Leone e il dominio del Sole. Purtroppo, non abbiamo menzioni rispetto all’Arnica. Sebbene tali affermazioni possano sembrare superstiziose vestigia di una certa influenza astrologica medievale, in realtà hanno dei significati ben precisi. Il segno del Cancro è legato al torace e allo stomaco, mentre il Leone al cuore (sia fisico che inteso come “centro” emozionale). Entrambi i segni astrologici indicano i distretti corporei per i quali i rispettivi rimedi presentano particolare affinità. Le erbe considerate “sotto il dominio di Venere” hanno specifiche attività: stimolano la rigenerazione tissutale e la moltiplicazione cellulare e sono capaci di “contenere” le manifestazioni di tipo marziale (come le emorragie e le infiammazioni), per cui risultano vulnerarie (capaci, cioè, di sanare le ferite) e demulcenti. Le erbe sotto il dominio del Sole agiscono, ad esempio, sul sistema nervoso e sulla circolazione del sangue. Mettendo insieme queste proprietà, vengono fuori caratteristiche peculiari per ciascuna delle piante: la Margherita, ad esempio, ha un effetto quasi specifico rispetto alle “ferite cassali” (ossia del petto), mentre la Calendula sostiene il cuore, sia nell’aspetto circolatorio sia in quello emozionale (ha attività antidepressiva). L’Arnica ha un’azione decisa sul muscolo cardiaco e sulla circolazione, specialmente arteriosa, e il suo effetto è tanto potente da risultare, come già detto, tossica.

Nell’antichità, tra gli indicatori principali delle azioni delle piante figuravano l’odore e, in misura forse maggiore, il sapore. Effettivamente queste sensazioni sono in grado di fornirci informazioni sulle sostanze contenute nelle erbe e soprattutto sulla “energetica” della pianta.

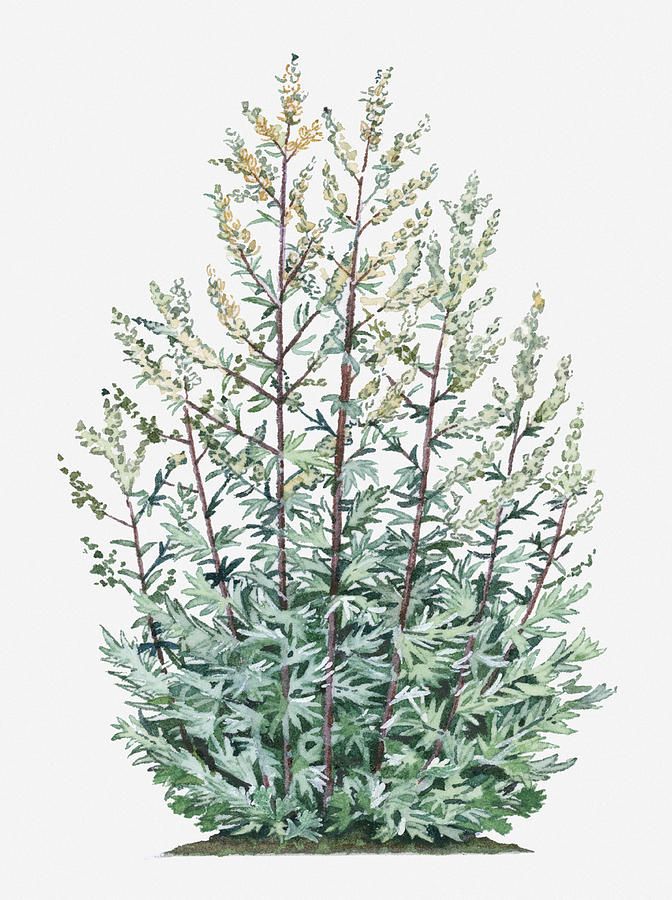

La Calendula è una pianta dal sapore decisamente aromatico e amaro ed inoltre è fortemente resinosa. È anche leggermente salata, dolce, astringente e acre, ma questi sapori sono meno importanti dei primi tre. Il suo profumo è balsamico ed erbaceo (più erbaceo nella Calendula officinalis e più balsamico nella Calendula arvensis).

La Margherita ha un profumo molto delicato: in realtà solo i capolini hanno un odore decisamente percettibile (le foglie hanno un aroma fugace che si avverte solo all’assaggio) e comunque si riesce ad apprezzarlo in maniera netta solo quando i fiori sono en masse (parecchi fiori insieme). Il sapore è decisamente più complesso di quello della calendula: la Margherita è mucillaginosa e ha un sapore peculiare che la fa risultare contemporaneamente acre (per saponine), acido (probabilmente per acidi organici) e salino; è un po’ come se questi tre ultimi sapori si fondessero a dare un’unica sensazione. Sapori minori sono: leggermente aromatico (fiori e foglie), amaro (rizoma), dolce (fiore e stelo), leggermente pungente (radice e fiore), astringente (rizoma).

Non avendo mai avuto la possibilità di assaggiare l’Arnica, non parlerò del suo sapore.

Il sapore aromatico e resinoso della Calendula (che è decisamente più forte nella Calendula arvensis, rispetto alla Calendula officinalis) è chiaramente caldo ed è un forte indicatore della capacità di questa pianta di riscaldare e mettere in movimento. La sua componente amara è invece legata alla sua capacità di purificare l’organismo e, in maniera particolare, di “assottigliare” la flemma (liquidi ispessiti e viscosi) eventualmente presente nei tessuti e nell’apparato digerente.

Il mucillaginoso della Margherita ne indica la capacità demulcente (ossia, sedativa delle infiammazioni ed emolliente per i tessuti, specialmente se irritati) oltre che diuretica. Il sapore salino indica la capacità della pianta di: ammorbidire i tessuti; ammorbidire i depositi di flemma preparandoli per l’eliminazione; favorire l’evacuazione delle feci (ammorbidisce la massa fecale); “entrare nei Reni” (secondo la MTC), agendo, tra l’altro, sul metabolismo degli elettroliti. Il sapore acre indica la presenza di saponine, che hanno un’azione per certi versi simile a quella del salato (anche le piante con saponine ammorbidiscono i tessuti e i depositi di flemma), ma lo fanno in maniera decisamente più intensa. Il sapore acido indica la presenza di acidi organici, che hanno un’azione rinfrescante e che sono capaci di “sedare” la tendenza infiammatoria tissutale e metabolica. Insieme, tutti questi sapori indicano la capacità della margherita di spegnere le infiammazioni e di lenire i tessuti irritati, di favorire l’evacuazione delle feci e la diuresi e di ammorbidire i tessuti induriti e la flemma viscosa e stagnante. Quest’ultima proprietà la rende capace di agire su tutti gli “indurimenti” corporei, tra cui scrofole, orzaioli, linfonodi induriti e addirittura alcune neoplasie, benigne o maligne: in letteratura sono riportati casi di azione importante e decisa su alcuni casi di cancro (soprattutto mammario; v., ad esempio, il Dr. J. Compton Burnett nel suo “Curability of Tumors”).

Entrambe le piante hanno una importante capacità antinfiammatoria. Da quanto appena esposto, si evince che però il meccanismo d’azione è differente: la Calendula, essendo calda, ha la capacità di “mettere in movimento” e questo lo fa anche con l’infiammazione, che viene letteralmente spostata dai tessuti e “dispersa” (la Calendula veniva addirittura classificata come “espulsiva”, cioè capace di espellere le malattie verso l’esterno del corpo); la Margherita, invece, “spegne” l’infiammazione e riduce l’eventuale sottostante iperattività tissutale.

Anche l’omeopatia, infine, ci dà alcune informazioni interessanti. Ad esempio, Bellis perennis viene suggerita nei casi in cui il gonfiore causato da un trauma permane anche dopo l’uso di Arnica, oppure nel caso in cui il trauma sia dovuto specificamente ad una operazione chirurgica, quindi un trauma “profondo” dal punto di vista tissutale (v. ad esempio [HForHealth, Vermeulen2]).

Bibliografia

| [Culpeper] |

Culpeper’s “Complete Herbal” (1653 & other editions) |

| [Durante] |

Castore Durante, “Herbario nuovo” (1667) |

| [Gerard] |

John Gerard, “The herball, or, Generall historie of plantes” (1636 & other editions) |

| [HForHealth] |

http://www.homeopathyforhealth.net/2012/10/24/bellis-perennis/ |

| [Mattioli] |

Pietro Andrea Mattioli, “Discorsi di M. Pietro Andrea Mattioli sanese, medico cesareo, ne’ sei libri di Pedacio Doscoride Anazarbeo della materia Medicinale” (1746) |

| [Vermeulen] |

Frans Vermeulen, “Plants – Homeopathic and Medicinal uses from a Botanical Family Perspective”, Saltire Books (2011) |

| [Vermeulen2] |

Frans Vermeulen, “The New Synoptic One”, Emryss (2004);

(Italiano) Frans Vermeulen, “Materia Medica Omeopatica Sinottica”, Ed. Salus Infirmorum (2007) |

[1] Erba da lividi.

[2] In realtà, l’uso di Arnica sulle ferite aperte è da evitare perché può produrre reazioni cutanee.

English Version

Arnica, Calendula, Bellis

Arnica, Calendula and Bellis are three botanical genera belonging to the Asteraceae (or Compositae, old name) family. Asteraceae is one of the two largest genera in Spermatophytae (plants that reproduces through seed), together with Orchidaceae, because these two genera contain the greatest number of species.

Due to the large number of species, the whole family has been subdivided into 13 subfamilies, and several tribes and subtribes. Arnica, Calendula and Bellis belong to the Asteroideae subfamily, and to different tribes. All of them have both ligulate and tubulate florets.

In both phytotherapy and homeopathy, these three genera and the respective most-known species, Arnica montana, Calendula officinalis and Bellis perennis, are probably considered the best remedies for both physical injuries and emotional traumas. According to David Little, the homeopathic remedies from Asteraceae can be divided into four groups (Arnica, Chamomilla, Cina and Wyethia) basing upon similarities in modes of action. The whole Arnica group (comprising the remedies Arnica, Brachyglottis, Bellis perennis, Eupatorium aromaticum, Eupatorium perfoliatum, Eupatorium purpureum, Calendula, Erechtites, Erigeron, Echinacea, Gnaphalium, Guaco, Lappa, Millefolium, Senecio aureus) is characterized by traumas, hemorrhages, septic states, arthritic and rheumatic diathesis and urinary concomitants (see [Vermeulen]).

Bellis perennis has never gained the same popularity as Arnica montana and Calendula officinalis, which are used every time a little or big trauma occurs, but the “humble” Daisy is indeed a quite powerful remedy that can be used more or less interchangeably with the other two ones, even though some differences obviously exist. In a first instance, we can describe Bellis perennis as a deeper-acting Arnica with some broader indications.

Before going on, let’s have a look at what the ancient authors say about these three plants.

Bellis

John Gerard [Gerard] tells about the “little daisies” (or “lesser daisies”):

“The lesser Daisies are cold and moist, being moist in the end of the second degree, and cold in the beginning of the same.

The Daisies do mitigate all kinde of paines, but especially in the joints, and gout proceeding from an hot and dry humor, if they be stamped with new butter unsalted, and applied upon the pained place: but they worke more effectually if Mallowes be added thereto.

The leaves of Daisies used amongst other pot-herbs, do make the belly soluble; and they are also put into Clysters with good successe, in hot burning feuers, and against the inflammation of the intestines.

The juice of the leaues and roots snift up into the noshtrils, purgeth the head mightily of foule and filthy slimy humors, and helpeth the megrim.

The same giuen to little dogs with milke, keepeth them from growing great.

The leaues stamped take away bruises and swellings proceeding of some stroke, if they be stamped and laid thereon; whereupon it was called in old times Bruisewort.

The juice put into the eies cleareth them, and taketh away the watering of them.

The decoction of the field Daisie (which is the best for physicks use) made in water and drunke, is good against agues, inflammation of the liuer and all other inward parts.”

Culpeper [Culpeper] writes about the greater wild daisy (Leucanthemum) and the small daisy (Bellis) in the same paragraph:

“[The Daisies] are so well known almost to every child, that I suppose it needless to write any description of them. Take therefore the virtues of them as followeth.

Government and virtues. The herb is under the sign Cancer, and under the dominion of Venus, and therefore excellent good for wounds in the breast, and very fitting to be kept both in oils, ointments, and plaisters, as also in syrup. The greater wild daisy is a wound-herb of good respect, often used in those drinks or salves that are for wounds, either inward or outward. The juice or distilled water of these, or the small daisy, doth much temper the heat of choler, and refresh the liver, and the other inward parts. A decoction made of them, and drunk, helpeth to cure the wounds made in the hollowness of the breast. The same also cureth all ulcers and pustules in the mouth or tongue, or in the secret parts. The leaves bruised and applied to the scrotum, or to any other parts that are swollen and hot, doth dissolve it, and temper the heat. A decoction made thereof, of wallwort and agrimony, and the places fomented or bathed therewith warm, giveth great ease to them that are troubled with the palsy, sciatica, or the gout. The same also disperseth and dissolveth the knots or kernels that grow in the flesh of any part of the body, and bruises and hurts that come of falls and blows; they are also used for ruptures, and other inward burstings, with very good success. An ointment made thereof doth wonderfully help all wounds that have inflammations about them, or by reason of moist humours having access unto them, are kept long from healing, and such are those, for the most part, that happen to joints of the arms or legs. The juice of them dropped into the running eyes of any, doth much help them.”

Mattioli writes:

“Bellis is a group of different types of plants, and it consists of three species, that is, major, minor and medium. […] Moderns commend all these species for scrofula, for wounds on the head, and similarly to soak up the bandages that are put upon the wounds of the chest that penetrate into the concavities of the thorax. The leaves, chewed, heal the ulcerated pustules of the mouth and of the tongue, and pounded and applied on the genital parts, heal their inflammations. The fresh herb eaten in salad soften the bowels, and the same does it when it is eaten cooked in meat broth. Someone uses Bellis for palsied, and also for sciatica.” [Mattioli]

Calendula

Gerard writes:

“The floure of the Marigold is of temperature hot, almost in the second degree, especially when it is dry: it is thought to strengthen and comfort the heart very much, and also to withstand poyson, as also to be good against pestilent Agues, being taken any way. Fuchsius hath written, That being drunke with wine it bringeth downe the termes, and the fume thereof expelleth the secondine or after-birth.

But the leaues of the herb are hotter; for there is in them a certaine biting, but by reason of the moisture joyned with it, it doth not by and by shew it selfe; by meanes of which moisture they mollifie the belly, and procure solublenesse if it be used as a pot-herbe.

Fuchsius writeth, That if the mouth be washed with the juyce it helpeth the toot-ache.

The floures and leaues of Marigolds being distilled, and the water dropped into red and watery eies, ceaseth the inflammation, and taketh away the paine.

Conserue made of the floures and sugar taken in the morning fasting, cureth the trembling of the heart, and is also giuen in time of plague or pestilence, or corruption of the aire.

The yellow leaues of the floures are dried and kept throughout Dutchland against Winter, to put into broths, in Physicall potions, and for diuers other purposes, in such quantity, that in some Grocers or Spice-sellers houses are to be found barrels filled with them, and retailed by the penny more or lesse, insomuch that no broths are well made without dried Marigolds.” [Gerard]

And Culpeper:

“[Marigolds] being so plentiful in every garden, and so well known that they need no description.

Time. They flower all the Summer long, and sometimes in Winter, if it be mild.

Government and virtues. It is an herb of the Sun, and under Leo. They strengthen the heart exceedingly, and are very expulsive, and a little less effectual in the smallpox and measles than saffron. The juice of Marigold leaves mixed with vinegar, and any hot swelling bathed with it, instantly gives ease, and assuages it. The flowers, either green or dried, are much used in possets, broths, and drink, as a comforter of the heart and spirits, and to expel any malignant or pestilential quality which might annoy them. A plaister made with the dry flowers in powder, hog’s-grease, turpentine, and rosin, applied to the breast, strengthens and succours the heart infinitely in fevers, whether pestilential or not.” [Culpeper]

Mattioli says:

“Some of the moderns affirm that Marigold […] is the Caltha of Virgil and Pliny, basing only upon the golden color of its perpetual flowers. […] In Tuscany we eat it in salads. Caltha warms, thins, opens, digests, and provokes, even if a little astringency can be perceived when tasting it: but it’s well known from the thousands of experiments done by women, that it frankly provokes the menses, and maximally when drinking its juice, or rather eating the herbs for some days. An ounce of the juice, drunk with a dram of pulverized earthworms, heals the jaundice. Someone says that using this herb sharpens the eyesight quite effectually, and it’s well known that the water distilled from the flowered herb heals the redness and the inflammation of the eyes when poured in them, or when applied onto them with some linen cloth. The dried powder applied onto sore teeth proves really profitable.” [Mattioli]

Castore Durante is a little more descriptive:

“QUALITIES. It’s hot and dry, and it’s more suitable to the external parts of the body than to the internal ones; it thins, opens, digests, provokes, even if a little astringency can be perceived when tasting it.

VIRTUES. Internally. It induces the menses, drinking the juice or eating the herb for some days. An ounce of the juice, drunk with a dram of pulverized earthworms, heals the jaundice. The leaves and the flowers are eaten usefully in salad, and, when put into broths, they confer a good smell and taste. This herb is useful in heart troubles, in difficult breathing, and in jaundice. An omelet prepared with the flowers and the tender tops and egg yolk stops the superfluous menses when eaten.

VIRTUES. Externally. The distilled water of its flowers and fronds takes inflammation away from the eyes, when it is instilled in the eyes or applied over them with a cloth, and sharpens the sight and it’s as good as that of blessed thistle and of scabious to the pestiferous diseases, and it’s cordial. The herb heals the wounds. The powder of the flowers, applied with cotton within an aching tooth, takes the pain away. The dried flowers and leaves, when used to fumigate the matrix, provoke the menses marvelously, and expel retained afterbirth. The flowers make the hair blond, when it is boiled in lye.” [Durante]

Arnica

Arnica montana is now one of the most known medicinal herbs. In classical antiquity, however, it was apparently not well known. It has been cited by Hildegard von Bingen, that called it “Wolfsgelegena”:

“Wolfsgelegena is very hot and has a poisonous heat in it. If a person’s skin has been touched with fresh Arnica, he or she will burn lustily with love for the person who is afterward touched by the same herb. He or she will be so incensed with love, almost infatuated, and will become a foul.” (Physica)

Some scholars have associated Wolfsgelegena with Arnica, because the description in Physica fits the one we know of Arnica, that is, an effective topical remedy for cuts, blisters, rashes, and pain, but some medical historians disagree about whether this was rather a reference to an herb with similar effects. Arnica is cited in the medical texts starting from 15-th century, but it’s only described and painted. At the end of 16-th century, Franz Joe from Göttingen suggests it for the cure of wounds. Even though Arnica has been cultivated in gardens since long, it seems that it has been accepted in pharmacies only about 1788.

More recently, abbot Kneipp wrote about Arnica basing upon its personal experiences, putting it on the top of the list of the wound healing herbs. In his book “Meine wassen-kur” (“My cure with water”), written in 1890, he wrote:

“the tincture of Arnica is so widely known and used for wound healing and in compresses, that I repute unuseful to write any word about it.”

Goethe was used to drink an Arnica infusion when he felt chest pain because of his cardiac insufficiency due to aging.

Since Arnica is not present in classical texts, it’s obviously difficult to know the nature (temperature) traditionally attributed to the plant. Anyhow, despite the uncertainty about the real identity of the plant mentioned by Hildegard von Bingen, Arnica can be likely regarded as “very hot and [with] a poisonous heat in it”, because of its properties (it stimulates the arteriovenous circulation and the cardiac activity; it’s revulsive, when used externally, and cholagogue, diuretic, emmenagogue, and abortive, when used internally), its toxicity and its specific side effects (gastric irritation with nausea and colic, despite the induction of paralysis of nerve centers).

Arnica has an analeptic activity (that is, it stimulates the nervous system) and such activity can be apparent even at homeopathic dilution for some people.

Differences between the plants

Even though it’s true that the three plants are often used interchangeably, especially for traumas and wounds (even septic ones)[1], some important differences exist between them. The first one is easily deduced from the classic authors and is related to the nature (or temperature) of the herbs:

- Bellis is cold and moist in the second degree (so, more than simply cool)

- Calendula is hot and moist

- Arnica is very hot and contains a poisonous heat.

So, we can tell that, going from Bellis to Calendula to Arnica, the heat degree increases considerably, so much that Bellis is decidedly cooling, Calendula warming and Arnica so hot to prove toxic.

Daisy action is, indeed, more resolutely directed toward sedation of inflammation, of pain and even of histamine-mediated reactions, so that it is particularly suited to “hot” diseases: inflammation, acute pain, redness, swelling (e.g., burns; painful traumas; purulent, hot and painful insect bites). The lack of heat in Daisy makes it not especially apt to “move fluids”: for example, it has not an appreciable emmenagogue activity, nor it is, consequently, abortive. Indeed, though the whole Daisy plant is apparently cold and moist, its flower heads contain a certain degree of heat, so much that they taste slightly pungent. This feature confers the Daisy flowers a certain diffusive and “moving” ability, that makes the action of the whole plant (that is, leaves, flowers and roots together) decidedly more complex (and complete). Daisy too, like Marigold (see below), for instance, can be used for septic wounds.

Marigold is warmer than Daisy, and so its action is decidedly oriented to movement: indeed, it stimulates the movement of both the blood (hence its emmenagogue activity) and the lymph. This is the reason why Calendula has a marked action on sepsis, so much that practice has proved to be effective in even important and difficult-to-treat infections. Its action is mostly due to its ability to act upon tissues and lymph system rather than to a directly antibiotic activity. So, Marigold probably has a greater effectiveness in preventing and treating sepsis and in inducing the menses, while Daisy has a stronger antiphlogistic and pain-relieving action.

Arnica is the hottest of the three plants, so much to prove rather toxic and decidedly abortifacient too.

The different heat degree is also linked to the “deepness” of plant action: since heat tends to superficialize, Arnica has a stronger affinity for the most superficial tissues (i.e., skin, muscles, and blood vessels), while Bellis has a stronger affinity for the deepest ones (chest, abdomen and body cavities). Calendula has an intermediate heat degree and so also its “deepness” of action is intermediate (it has an important effect upon the body fluids).

Another noteworthy difference lays on the plant tropism. Culpeper tells that Daisy is an herb under the sign of Cancer and under the dominion of Venus, while Marigold is under the sign of Leo and the dominion of Sun (unfortunately we have no similar information about Arnica). Even though such statements may appear superstitious remains of a certain medieval astrologic influence, in fact they have well defined meanings. The sign Cancer is linked to thorax and stomach, while Leo is linked to the heart (both physical and emotional). Both the astrological signs define the body districts for which the respective remedies have special affinities. The herbs said “under the dominion of Venus” have specific properties: they stimulate tissue regeneration and cellular division and are able to “stem” any martial event (like hemorrhages and inflammations), so that they are vulnerary (that is, able to heal wounds) and demulcent. The herbs under the dominion of Sun act, for instance, upon nervous system and blood circulation. Putting these properties together, some specific features arise: Daisy, for example, has an almost-specific action upon chest wounds, while Marigold supports the heart, both in the circulatory and in the emotional aspects (it has an antidepressant action). Arnica has a firm action upon the cardiac muscle and upon circulation, especially the arterial one, and its effect is so powerful to prove, as already told, toxic.

In the antiquity, smell and, possibly to a greater extent, taste were the most important indicators of the actions of the plants. Indeed, these sensations can provide us with a lot of information about the class of chemical substances contained in the plants and, above all, about the “energetics” of the plants.

Marigold has a decided aromatic and slightly bitter taste, and it’s quite resinous. It’s also slightly salty, sweet, astringent and acrid, but these tastes are less relevant than the former three. Its odor is balsamic and herbaceous (more strongly herbaceous in Calendula officinalis and more balsamic in Calendula arvensis).

Daisy has a faint smell. Only the flower heads, indeed, have a perceptible odor (the leaves have a fugacious flavor that can be perceived only when the plant is chewed) that can be felt neatly only when the flowers are en masse (several flowers together). The taste is decidedly more complex than that of Marigold: Daisy is mucilaginous and has a peculiar taste that make it acrid (because of saponins), acid (probably because of organic acids) and salty at the same time; it’s as if these three tastes combine in a single mouth sensation. Minor tastes are: slightly aromatic (flowers and leaves), bitter (rhizome), sweet (flower and stalk), slightly pungent (root and flower), astringent (rhizome).

Unfortunately, I have never tasted Arnica, so I will abstain from speaking about the organoleptic properties of this plant.

The aromatic and resinous taste of Marigold (stronger in Calendula arvensis than in Calendula officinalis) is clearly warm and hints to the plant ability to warm and “put on movement”. Its bitter component is linked to the herb’s purifying action and, particularly, to its ability to “thin” phlegm (thickened and viscous fluids) possibly stored in tissues and in the digestive system.

The mucilaginous taste of Daisy suggests a demulcent (that is, able to sedate inflammation and to soothe irritated tissues) and diuretic ability. The salty taste indicates that the plant softens tissues; softens phlegm accumulations, “preparing” it for elimination; promotes stool evacuation (softens the fecal mass); “enters the Kidney” (according to TCM), acting, among other things, on the electrolytes metabolism. The acrid taste is due to saponins, and it exerts an action similar to that of salty (also saponin-containing plants soften the tissues and the phlegm), but even stronger. The acid taste suggests the presence of organic acids, that possess a refreshing action and the ability to “quench” the tissutal and metabolic tendencies to inflammation. All these tastes together point at the Daisy’s ability to resolve inflammation and soothe irritated tissues, to promote stool evacuation and diuresis, and to soften indurated tissues and the viscous and stagnating phlegm. The latter properties make the Daisy able to act upon all the body “indurations”, for instance, scrophula, sties, hardened lymph nodes, and even some benign or malignant tumors: some cases are reported in which Daisy exerted an important and decided action upon some forms of cancer (especially of the breast; see, for instance, Dr. J. Compton Burnett in his “Curability of Tumors”).

Both Daisy and Marigold have an important anti-inflammatory effect, but, at this point, we understand that the mechanisms of action are quite different: Marigold, being hot, is able to “put on movement” inflammation, that gets literally moved from tissues and “dispersed” (Marigold was once classified as an “expulsive”, that is, a remedy able to expel disease out from the body); Daisy, instead, “quenches” inflammation and reduces the possible underlaying tissutal hyperactivity.

Homeopathy gives us some more interesting information. For instance, Bellis perennis is recommended in those cases when the swelling (of a traumatic origin) doesn’t resolve after using Arnica, or when the injury is specifically due to surgery, that

[1] In fact, Arnica should not be applied onto open wounds, due to a certain risk of inducing skin reactions.

*Pierluigi Campidoglio of HWB Italy: I’m a chemist, a farmer (I grow veggies, aromatic and medicinal plants) and a herbalist. After the graduation in chemistry (2000), I’ve been studying massage, naturopathy and traditional chinese medicine (theory, chinese massage AnMo-TuiNa, moxibustion, acupuncture, cupping, shiatsu, …) from 2005 to 2011. After that, I have kept studying, focusing mostly on homeopathy, nutritional therapy, herbalism (especially traditional chinese phytotherapy and traditional mediterranean herbalism) and crystal healing. I’ve finally obtained my herbalist and phytotherapist diploma in 2016.

Find out more: https://www.facebook.com/alleanzaverde/

Nei prati di San Severino Marche cresce un “cardo” che cardo non è! Il “cardo asinino” (Cirsium vulgare Salvi (Ten.) subsp. vulgare) presenta uno splendido colore caldo, purupureo nella corolla. Rivestito di spine pungenti, forma tuttavia un fiore delicatissimo, profumato, spesso visitato da api e bombi.

Nei prati di San Severino Marche cresce un “cardo” che cardo non è! Il “cardo asinino” (Cirsium vulgare Salvi (Ten.) subsp. vulgare) presenta uno splendido colore caldo, purupureo nella corolla. Rivestito di spine pungenti, forma tuttavia un fiore delicatissimo, profumato, spesso visitato da api e bombi.